“Need a bog, old boy?”

I had no idea what I needed. Sixty hours prior, I was on a Pan Am flight to London, seated next to a petite, blond woman of about my age, with short-cut hair, dressed in deep green, and speaking with a distinct Scottish accent. Much later, I would learn it was Glaswegian, the local dialect in Glasgow. I struggled to understand what she said above the roar of the jet engines outside our window as she questioned me about my destination and the reason for my journey: “Wales, the university college in Swansea. I’m going to be an oceanographer,’ “I said, filled with expectations. She shrugged and said something like, “Lovely, it rains a lot there—very green place.” We both turned to our dinner. The lights dimmed, and she slept. I was too excited to sleep, but eventually exhaustion triumphed and I dozed off. When the lights came on again, we were over Ireland, and breakfast was in front of me. As we finished, she said, “That’s Wales down there - see the green!” I bent over her seat to look. The scent she wore was earthy, smoky, leathery, mixed with tobacco from the cigarettes she smoked. Distracted, I’m not sure I really saw Wales. I thought of William Blake’s poem and anthem, “Jerusalem.’”1 In the years I spent in Wales, it was commonplace to hear it sung in Pubs, spontaneously with the rich choral voices you only hear in Wales. I had the feeling of finally coming home. It was a strange feeling.

We landed at London Heathrow just before 7:00 AM, disembarked on the tarmac, and walked to Immigration and Customs. At Immigration, we parted ways where British subjects took a shorter, faster line, and “Others” took the long, slow one. She touched my arm and, on tiptoes, kissed me on the cheek, whispering, “Good luck with your becoming.” And with that, she vanished. Her name was Glynnis. I never saw her again.

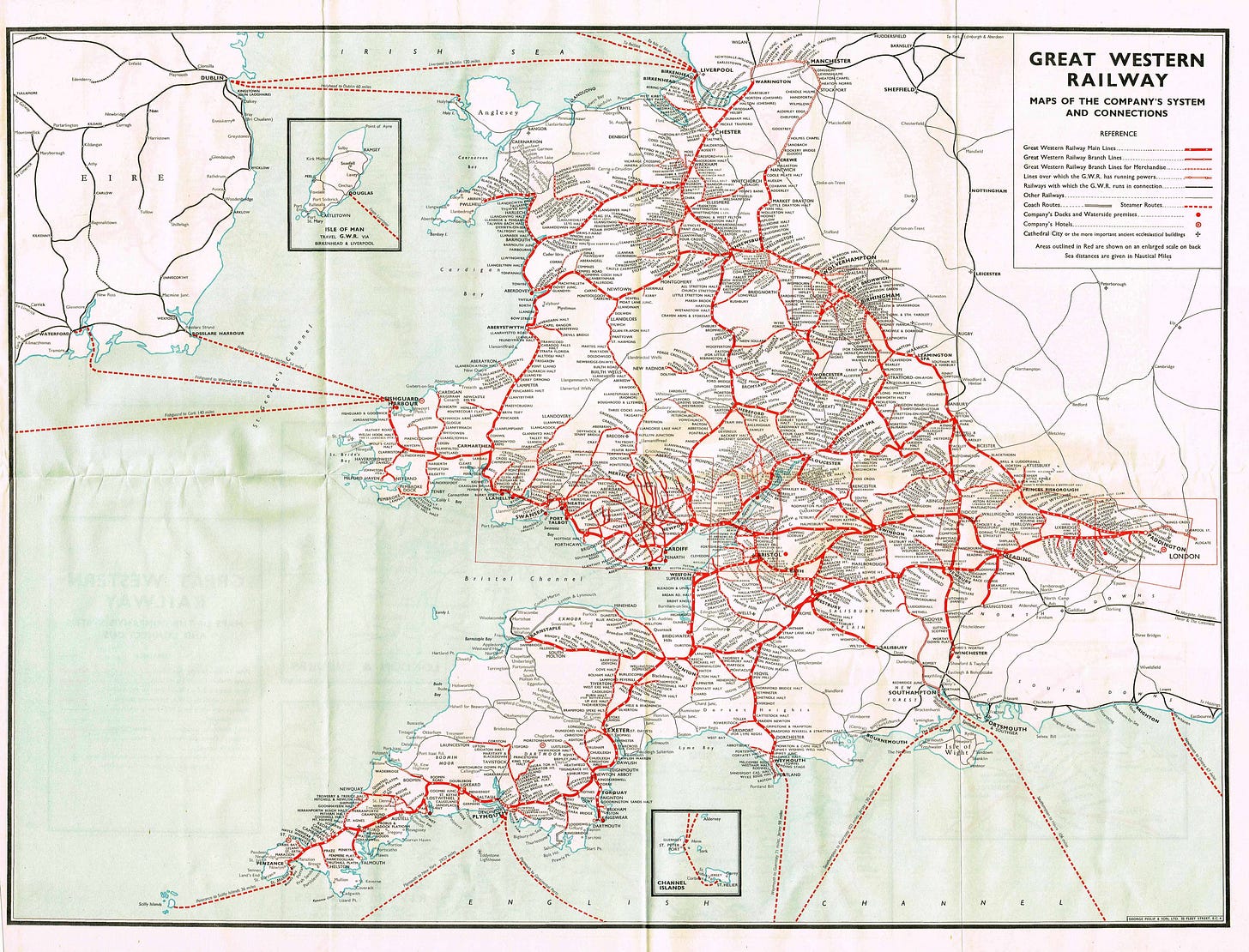

Once I cleared Immigration and Customs and received instructions on what I needed to do as a resident alien, I caught a cab to Paddington Station for the final leg of my journey to Swansea, about four hours away on the Great Western Railway (GWR). I learned about this railway’s history, which began in 1838, from my father, who was an engineer with Bell Telephone and a great admirer of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Brunel is one of the significant historical figures of the Industrial Revolution. His feats of engineering laid the foundations for modern transportation infrastructure and material design, and are evident everywhere in Britain.

Ticket in hand, I boarded the passenger carriage and looked for my seat in the compartments that lined a long, narrow passageway. Mine was empty, and I took a seat at the window, watching people board, the porters, and the conductors to see when we would depart. A well-dressed gentleman entered the compartment, then a woman with two young children. They all sat on the bench opposite me, staring and taking my measure. The oldest child sat on my side, as far away from me as possible. Whistles blew, and with a jolt, we were on our way as conductors boarded and began collecting tickets.

No one spoke. It was at the stop in Reading when the gentleman asked where I was going. “The University at Swansea.”

“Ah, You’re American.”

“Yes. It’s my first time here.”

He smiled, “Not many Yanks in Swansea.” The woman looked at her children, “He’s American, Evan. Going to Swansea like us.” Everyone smiled in my direction. Then she took out some sandwiches and what looked like sausages in puff pastry, and she and her children had lunch. The gentleman opened his newspaper. That was it, and we started again, swinging north towards Swindon. My stomach rumbled a few times. I hadn’t eaten since breakfast on the plane. During the stop at Bath, the gentleman left for a while, and when he returned, he said, “There’s food two cars back.”

“Thanks,” and I left to head in that direction in search of a meal. Several passengers were in the dining car, and I made my way to the counter. The choice of beer was easy, but the options for other food were a mystery. I recognized the sandwiches, but they looked plain and stale - just cucumber and bread. I chose a thick slice of pork pie (with egg inside), a sausage roll similar to those the children ate, and a piece of cake, much like what others in the car were eating. “When in Rome, etc.,” I thought. To this day, I love pork pies with Branston Pickle. Cold Sausage Rolls are tasty but hard on an empty stomach. We passed through the Cotswolds and arrived at Bristol.

I returned to the compartment and quickly fell into a deep sleep as we passed through Cardiff, Penarth, and Barry. I awoke, and we were in Wales. Now I was full of anticipation as we slowly made our way through the small villages and towns, set amidst coal mines in the heart of valleys running North and South. The landscape was grey and foreboding, reminding me of Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier. Further on we passed through Port Talbot and Neath, and at last Swansea. The gentleman was long gone while I slept, but the woman and her children remained. They lived in Swansea, and as they exited, she wished me well and pointed out where I could find a nearby hotel. She was reserved but very kind, and I loved the musical sound of her soft, lilting Welsh accent, something I came to love most about the people I lived among in Wales.

It was about two o’clock in the afternoon as I made my way to find a room at the Swan Hotel. Once settled in, I found a bus to the University College campus at Singleton Park. The road ran alongside the broad beaches of Swansea Bay. I got off at the entrance of a modern “Red Brick” University. The Zoology, Geology, and Botany Departments were in a new building that faced out over the Botanical Gardens. My mentor was to be Professor Ellis Winn-Jones, the Professor and Head of the Department of Zoology. We had corresponded extensively before his last letter convinced me to come and study under him. It was spontaneous. Less than two weeks ago, I had said yes to his offer, sold my car, and bought a ticket to London, and now I was in his office. His secretary, Mrs. Holden, said he was not in as he was preparing for the week-long third-year field trip to Bangor and Anglesey. He wanted me to go as a teaching assistant and would pick me up at the Department the following day at 10:00 a.m.

My to-do list was long and complicated, but I had to be ready in time, and, worst of all, I knew nothing about the coastal and intertidal zones of Great Britain, where the tidal range could be 10 meters. Mrs. Holden graciously provided me with a list of places where I could obtain digs (room and board) and shops where I could purchase clothing and Wellies (rubber Wellington Boots) needed for work in the intertidal zones of Bangor and Anglesey. I found a guide to the intertidal in the Commons bookstore. With that, I was off, finding my way, a stranger in a strange land, nervous and uncertain.

Digs proved easiest of all. I caught a bus along the coastal road that ended near the islets known as The Mumbles. I stopped in Oystermouth, in front of the Rose and Crown Pub. Halfway up the Oystermouth Road at 127, I met Mrs Grace Evans, my future landlady. Her last available room was on the third floor, and its heavily draped windows looked out on the ruins of Oystermouth Castle. There was a fireplace with an electric fire and a bathroom with a tub and hot water on “demand.” Both appliances needed shillings to get heat and hot water. Showers were rare in Britain at the time. The room was bright and sunny, with a desk and a bookcase situated in a small alcove. It all came with a full breakfast every morning, as well as dinner and breakfast on weekends. I was stunned by how inexpensive it all was. Time would prove that the days that were bright and sunny in my room were rare, and through the winter, more often it would be damp and cold. It took a lot of shillings, but you could make toast on the electric fire and have hot water for tea. Mrs. Evans informed me that her husband, Evan, a policeman, would be able to collect my belongings from the hotel the next morning, and the room would be ready for me upon my return from Bangor. The rest was easy. I had an early dinner at the hotel and later read the intertidal guide cover to cover before going to sleep.

I was starving the next morning, but the full breakfast at the Swan Hotel was more than adequate. I gathered my gear and a backpack with some clothes and caught the next bus to the campus. Knight-Jones was waiting in the parking spaces reserved for deliveries in the Botanical Gardens. I learned later that this was the source of an ongoing feud with the Professor of the Botany Department, compounded by the fact that Knight-Jones had discovered, named, and published on the genus Micrococcus, the smallest known single-celled phytoplankton, measuring 1 micron in diameter. A zoologist describing a plant genus of all things! Rivalries in science are often as trivial and inexplicable as this. We loaded his car and, with my help, lifted the garden gates off their hinges to get out.

His car was a beautiful tan 1953 Austin A70 Hereford, wood-paneled on the sides and rear; the British version of what we called a “Woodie.” It was 11 years old, and unusual for the immediate post-war era in Europe, where most vehicles were pre-war and could be hand-cranked. The journey to Bangor took approximately four hours. We would arrive around 5:00 p.m. Prof was in no rush.

We took a turn West, crossing the Burry Estuary, where women with their donkeys harvested cockles on the mud flats at low tide,2 then headed towards the beaches at Llanelli. We stopped there and got out. It was low tide, and the flats were exposed.

Prof looked back and said, “Put your boots on, and grab the shovel.” Dutifully, I followed. “Can you smell it, old boy?” “No, I all I smell is iodine.” ‘Eureka! That’s it, Saccoglossus is here.” “Wonderful,” I said, not knowing what he was talking about. Soon, I would learn. “Here, he said, start digging and be careful not to cut it in half.” It turned out that Knight-Jones was not only known for his discovery of the smallest known phytoplankton, but he was also better known for his work on the genus Saccoglossus. His doctoral thesis at Jesus College, Cambridge, was on the genus and two species he discovered and named.3 He was elated as I dug deeper and deeper, eventually excavating a specimen over a meter long. I’d rarely seen anyone so happy, or a worm that size.

We resumed our trip, heading North in the direction of Llannon, passing the Bronze Age standing stone at Bryn Maen, and reconnecting with our originally intended route near Cross Hands. Prof was now in lecture mode, and he carried on for what seemed an eternity, but we were heading towards Bangor. Then the question, “Need a bog old boy?”, just before Cross Hands. I was rapidly learning how best to cover up my ignorance, defer and wait, keeping options open, being patient, listening for the meaning. “No, I think I’m OK,” I said. Silence, then, “Well, I think that I do,” he said and pulled over to the side of the road and wandered off into the wooded underbrush to pee. “Well, since you’re stopping, I might as well have one too.” He smiled at me, and I’m sure he knew what I was up to. Knowing colloquialisms and local slang is essential if you’re a stranger and want to fit in.

As we continued, we passed through Snowdonia (Eryi National Park), where I would later return to climb in the mountains with my newfound friends. Shortly before reaching Bangor, we passed through Bethesda and the Penrhyn Quarry, where the slate used for roofing and the tombstones in Britain all came from. It’s now a national historic site. The Welsh poet Dylan Thomas came to mind, and I remembered where he mentions it in his poetic play, Under Milkwood, describing the night in the fictional Welsh village of Llareggub as“a glee-party singing in Bethesda Graveyard.” Part of the beauty of Wales is its poetic soundscape.

We arrived at the hostel in Bangor, where the students and staff were staying, just before dinner. Students and faculty stayed in the main building, and four of us were to sleep in two small caravans parked next to what was called the “loo,” essentially a more formal structure for a “bog.” The grad student sharing the caravan with me introduced himself as Singhraja, a slim, serious man from Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, the son of a wealthy tea and coffee plantation owner. He was to study the effects of gravity on the behaviors of zooplankton with the Senior Lecturer at Swansea, Ernst Naylor. Over time, as I came to know him, I learned that his name meant “lion king.” He taught me a great deal about his world, his country’s politics, and his beliefs. He was a good and important friend. We all called him Singh.

That evening, we ate at a long table that accommodated all 30 undergraduate students, instructors, and support staff. The seating was tight and cramped on the benches, and I sat between Knight-Jones and Naylor. My eating habits were American, switching knife and fork as I ate, and that posed a problem. I kept poking elbows with Prof and Naylor. It was awkward, and clearly, I was the source of the problem. Prof leaned in and casually said, “Tell me, old boy, what do you know about the evolution of mimicry4 and cryptic coloration?” He smiled, and I looked around. Everyone else at the table was eating with their fork in the left hand and their knife in the right hand. No switching back and forth. No elbowing. Simple and effective. I whispered, “Got it.” He smiled and asked how I liked the meal as I switched hands and fell in line. There’s always something new you can learn, even elementary things. Prof was a sage and subtle teacher.

The night had turned very cold, and the overcast sky made it difficult for Singhraja and me to reach our caravan. Inside, there was only a dim flashlight for light, and we stumbled around as we found our way into the bunks and went to sleep. It was freezing. I slept in my clothes. In the dark, I could hear Singhraja shivering and his teeth chattering. He wasn’t used to this kind of cold coming from a tropical country. I gave him the heavy docker’s coat I had brought in Swansea as an added blanket, and we finally fell to sleep. The next morning was bright and sunny as I woke to the smell of coffee and toast. Singh has his coffee and tea that his family sent him. It was terrific, unforgettable. I teased him a bit as we drank and ate. He smiled and laughed. It was a beautiful day.

After breakfast, we took the class to the Menai Strait to explore the intertidal zone, collect specimens for the laboratory exercise later, and study the local ecology. The Strait is now part of the Conway Special Area of Conservation due to its unique ecology, diverse intertidal life, and physical and environmental conditions. Sheltered from strong wave conditions, it favors diverse seaweed growth. Tidal flows can reach speeds of 4 meters per second, carrying significant amounts of suspended matter that support a diverse array of filter feeders. These conditions, along with the varied substrates, foster an abundance of marine life and bird species. No amount of cramming with my intertidal guide had prepared me for this. The students knew far more than I did at the time, but by observation, listening, and keeping copious mental notes, I gained a degree of competence by the end of the week. I was new to all of this, and it was hard work and a serious challenge.

On the last day, as we packed up for the return to Swansea, it clouded over and began to rain. I know it can’t possibly be entirely true, but I swear the rain didn’t stop until Easter the following year. Glynnis was right, it rains a lot in Wales.

Almost all the people I came to know during my years living in Britain — students, friends, colleagues, and mentors — I first met in this week at Bangor, where my future began. The journey and my memories as an adult begin here, all because of a choice at the crossroads in my life. A choice that I had neither rhyme nor reason to know where it would lead.

To be continued. There is much more to tell. I hope you follow.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/And_did_those_feet_in_ancient_time%23:~:text%3DThe%2520poem%27s%2520theme%2520is%2520linked,there%2520was%2520a%2520divine%2520visit.&ved=2ahUKEwjv3-OKjKmOAxXAD1kFHaGSLK0Q-NANegQIGhBf&usg=AOvVaw1LR_IL4KGn2N13n7puFdOq

I came to like these particular cockles with ale at the Greyhound Pub on the Western side of the Gower Peninsula. They are large and fat, sweet, because of a naturally occurring parasite that sterilizes the males as they mature.

Saccoglossus is a genus of marine worms belonging to the class Enteropneusta, commonly known as acorn worms. They have a distinctive body shape, featuring an acorn-shaped proboscis, a collar, and a trunk. They feed by absorption through the body wall, and inhabit coastal mud and sand, where they burrow into the substrate. The smell of iodine is due to the excretion of iodine crystals from seawater, which line the walls of their burrows.

In biology, mimicry is a phenomenon in which one organism evolves to resemble another organism or an inanimate object, thereby gaining a survival advantage. Some butterflies evolve to resemble others that are toxic to birds, and as a result, birds avoid them. The stick insects are another example. Cryptic coloration, also known as camouflage, is an adaptation that enables an organism to blend in, making it more difficult for predators to spot it. It can involve matching the background color or breaking up the animal’s outline with disruptive patterns. By adapting these evolved traits, humans have also learned to do the same.

Lovely reading your reminiscences about your Swansea adventure--it evokes memories of my experiences in Villejuif and later, Vienna and beyond. These are transformative experiences and I'm sure that over the years you've encouraged your student to follow along.