Opening Doors, Seeing Through Windows

We are born into the world as it is, and in that moment, we are swept onward in the currents of time toward an unknown future. As our consciousness expands, we become aware of the fleeting present, possible futures, and our specific past. Each is important to how we construct our reality and its meaning at the moment, and each is deeply rooted in connections of place and family, our kith and kin. Through this rootedness, we are connected to people and their stories, gifts of time, and ways of seeing, which reveal the dynamic character of time and the human progress that emerges. Each story can be a revelation.

While watching the Paramount + spinoff of the Yellowstone series, 1923, I told my wife, Lynda, “You know, my father was 15 years old when this was all happening.” My entrance into this same timeline is only 19 years later. It’s striking how the world changed so quickly from my father’s birth to mine: the First World War, the Great Depression, and the Second World War. I’m fascinated by things like this and always want to know who else was alive at any given time, where it was taking place, who else was there, what they saw, and what changed the world.1 Knowing family histories can provide a window into the cause and effect of a changing world. Each ancestor reveals a time and place we cannot know otherwise, and we are enriched by their very existence and the knowledge that comes from them to us. Understanding the people and places we come from is the beginning of our capacity to see the world and know how it came about. This is an essential aspect of human evolution, the transmission of knowledge, recorded or verbal, from generation to generation.

I first became aware of the importance of this reading Frederic Morton’s Thunder at Twilight, an historical vision of Vienna and the two years that preceded WW I in a city filled with the likes of Freud, Mahler, Stalin, Trotsky, Lenin, Hitler and a multitude of other, significant historical figures embroiled in a turbulent stew of politics, art, science, ideologies, and untested theories.2 Where and who, context, and characters matter as progress over time constructs the reality of our world today; the stories of a changing world are the essence of our library of kith and kin, our rootedness in time.

Stories of People and Places

If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten. Rudyard Kipling

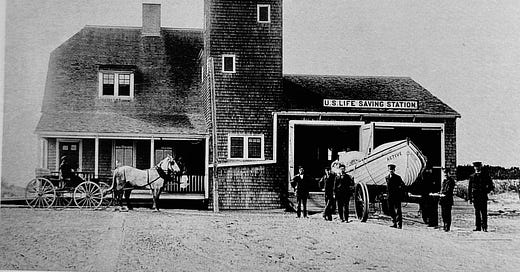

On the morning of December 30, 1912, the seagoing tug Margaret, with three heavily laden barges in tow, made way in a 45-mile/hour gale en route from New York to Norfolk, Virginia. It struck a submerged obstruction off the New Jersey coast, severely damaging the hull. Unable to make headway, the barges were cast off, and the vessel ran towards the shore to avoid sinking, grounded in the breakers several hundred yards from the beach. Four miles northeast, the lookout at the Avalon Lifeboat Station saw the wreck. Further to the south, at Tathams Station, a surfboat crew was assembled since the winds were more favorable for a southern approach. The keeper and crew from Avalon traveled by foot down the beach to Tathams to assist.

The first boat out from Tathams was engine-powered, with the crew manning oars. With some difficulties, the lifeboat breached the breakers. It approached the Margaret under power and oars several times for over a half-hour, gaining and losing repeatedly as the gale approached near hurricane force. The exhausted crew made one final approach and capsized when caught in a sudden wave of great force. Five of the keeper and crew clung to the lifeboat while two others at some distance swam for the shore. As the seas worsened, those clinging to the lifeboat gave up and struck out for the shore. Eventually, all hands reached safety near Avalon, assisted by friends and neighbors.

By 2:00 PM, the wind moderated somewhat, shifting westward, and the Avalon keeper, Frank Nichols, assembled his crew for a second approach. The eight-oar surfboat launched successfully and made headway to the Margaret. Relying on the strength of the oarsmen alone without power handicapped the approach, and they were swept helplessly past the wreck, forcing them to beat back windward on a second approach of more than 300 yards. The Margaret was now breaking up and in great danger when the lifeboat passed under the bow and successfully shot a line to the crew. As the line tightened, the lifeboat swung about broadside to the current and was battered by a succession of waves filling her with water and sweeping away five oars. The two keepers handling the steering oar managed to right the craft by strength alone. Held in this position, the crew of the Margaret tumbled quickly into the lifeboat.

As the last man off fell into the boat, a giant wave lifted the lifeboat and smashed it into the hull of the Margaret, staving in three planks of the surfboat hull. The crew managed to cast off and back away and made way to the shore with three oars and eighteen men on board. One crewman from the Margaret perished early in the grounding, but all others survived. Keepers Harry McGinley and Frank Nichols were awarded the Treasury Life Saving Gold Medal with letters from the Treasury Secretary.3

Frank Nichols was my great-grandfather. As a child, I would play in the abandoned ruins of Tatham Station at Stone Harbor. I only knew him when I was very young, a man who seemed frighteningly harsh at first sight, always with his Scottish Terrier. He was forever gentle and kind to me. He had lost the lower half of his right leg in his service but never seemed to mind. Had he not survived, I would never have existed. He and my great-grandmother, Hettie Douglas Nichols, who lived well beyond 100 years, are the people who are my roots, the place my ancestors have inhabited since the beginnings of this country. They are the doorway to my kith. I would have known nothing of this had I not stumbled across the medal received by my great-grandfather, framed and hanging in my great-aunt’s home.

The Sense of Place

We understand our kith through the history of our ancestors and occasionally through the conception of a fore-life, a sense of being in a place before, perhaps in an earlier life. That may sound strange, but it is within the realm of human experience - the sudden familiarity of a time and place where you were never there before. In the motion picture Patton, starring George C. Scott, this phenomenon of a fore-life appears throughout the film as Patton experiences the sounds and sensations of ancient battles when he is in places where they have occurred. Perhaps illusionary, but a sensitivity to a place not uncommon for many of us, including myself. More of that later.

Who I am is not solely a matter of genetics, although that is important. What I have become in my lifetime and how that is determined raises similar questions, although genetics is less critical. Chance, circumstance, and ancestry appear more influential. All of this suggests that the determinative questions we raise about our path in life need more profound consideration. With the understanding that an unexamined life is not worth living (Socrates?), let us see.

My ancestry on my father’s side has been populated with these names: Hand, Scull, Douglas, Crawford, Nichols, and Taylor since the earliest beginnings of European settlement in America. Hand is among the earliest, and Taylor was more recent at the end of the 19th century. I have often joked with my wife that there is a cemetery in Cape May County, NJ, where most of the dead seem to be related to me. Cape May County is where all of these names are gathered; although a few are scattered elsewhere in our country, most came to this place and settled there, staying for hundreds of years.

The overwhelming number of these ancestral lineages pursued their livelihood in the Sea. Initially, as watermen and coastal whalers who followed their prey as its population center moved southward from the early New England coasts to finally rest in the Cape May area of southern New Jersey, and from that location, as merchant seamen and sailors as the whales slowly retreated. The skill for this set is ubiquitous and passed through generations. As a young boy, my father taught me first to know the nighttime sky, the constellations, planets, and the important stars, and then how to use a sextant to navigate and determine where I was. Along the way, and without any awareness on my part, he taught me how to use navigation tables and to understand trigonometry. He would tell me, “If you don’t know where you are, you don’t know where you want to go. Your position in life is everything.” This rings true in more than one sense for one’s origin, the journey, and the destination. My origin, roots, and kith ground me in preparation for the journey.

In the early mid-19th Century, Robert Taylor immigrated from England to America with his wife and two sons. The 1850 Census, some years after their arrival, describes Robert as an “Editor” by profession, living in the First Ward of Manhatten, with two additional children born in the United States: a daughter, Jane, and a six-month-old son, Edmond Pierre born in 1850, my second great-grandfather from my father’s family. By the 1870 Census, Edmond lived in Atlantic City, working as a “waterman.” He later married Anna Scull and lived in Cape May, where he was a thriving maritime trader in the Caribbean Trade and owner of a three-masted brigantine.4 His only son, Edmond Pierre, left school at seven to work with his father. At age 22, he married Erma Hand Nichols and was the master of a sailing vessel, The P.T. Barnham. Shortly after, the P.T. Barnham sank in a hurricane off the coast near Staten Island. My grandfather was one of only four survivors. Had he not, I would not exist today. Something of an autodidact and possessor of a photographic memory, my grandfather went back to school. He received a degree in engineering and later worked for New Jersey Bell Telephone Company until retirement. He last worked on missile guidance systems as a contractor in his eighties.

My great-grandparents, Frank and Hetty Nichols, raised my father in his early life, and because of this, he was deeply connected to the place of his ancestors, his kith. It was in the coastal environments of inlets and marshlands that he acquired his early skills and knowledge, constructed his internal maps of places, people, and the environment, and internalized the rhythms of daylight and darkness, the heavens and the coming and going of the tides, and the where and how and when of all the complexities of nature and the world around him. He delighted in all that, passing it to me in a manner of thought and teaching I only fully understood long after his too-short life had ended. If it is true that the people who nurture us are always with us, then I can say his voice and presence follow me many years after, and who I am is a reflection of that. In all the history of my kith and kin, it is no wonder that I followed a path that led to a career as an oceanographer and professor. I am drawn to the world of oceans and marshes, the distinctive scent, the movements, the sunrises and sunsets, the stars and constellations, and knowing my place and being made whole because of it.

When we first meet others, the most common question we ask is, “Where are you from?” The answer is not always as simple as it seems. In 1964, I left the United States to study in Great Britain. On the flight over, I vividly recall it being a clear day. As we approached Heathrow in London, I glanced out the window at the lush green landscape of Devon and Cornwall. At that moment, I heard, “We’re home,” and a sudden calmness inside told me I was. That thought has never left me. Later, in 1967, when I went to study at the Marine Biological Association Laboratory in Plymouth, England, I discovered that more than 100 years after Robert Taylor emigrated from England, I had returned to his place, his kith. Deep inside, I knew I was home, in Plymouth, where there were more Taylors than any other name in the phone book.

The places of our ancestral past resonate within us in mysterious ways, and we cannot fail to understand their meaning or ignore the fact that we all have shared histories that bind us as indivisible people regardless of where we call home. That, to me, is our strength and the promise we undertake for our descendants. If we lose it, we lose everything. Without our place, we are adrift. Only chance and circumstance determine if we are here at all.

“… the markers we search for on the banks of time’s river motivate us in mysterious ways. Standing on the precipice of this very instant, we stare into the abyss of the eternal.” William Egginton, The Rigor of Angels. 2025.

The historical depiction of times past in contemporary video and films such as Yellowstone: 1923 and Peaky Blinders reveals how rapid our progress was in the 20th century and the challenge such an enormous leap poses for us today. We have become more separate and alone while simultaneously being more connected yet distant and dependent. It is paradoxical and disturbing.

In the same way, David Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East is the same idea. The book's preface opens on a private yacht in the Mediterranean Sea, the venue for a meeting of the few elites who sculpted the geography and politics of the Middle East that we experience today.

The Lifeboat Service preceded the Coast Guard Service and was originally under the Treasury Department. Today, the Coast Guard is under the Department of Homeland Security. This account is based on the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Digital Library. http://www.history.uscg.mil/library

Please see my earlier post, The Immigrant in the Mirror, on January 23, 2025.